Article by: Nakeria Woods, Contributing Writer.

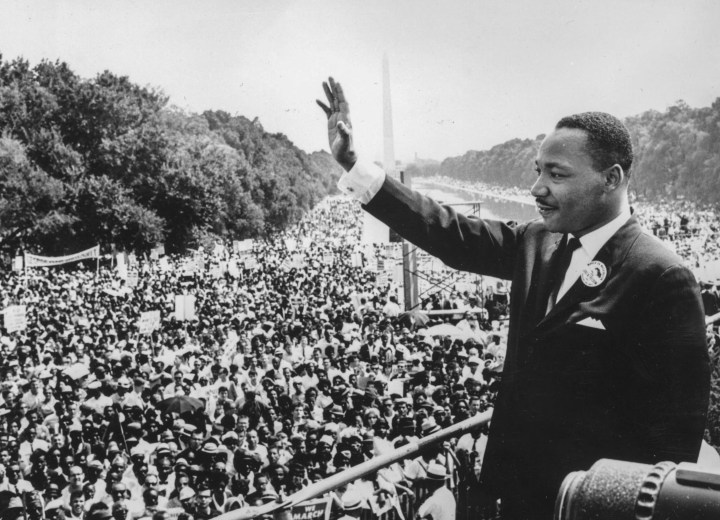

On every third Monday in January, the federal government recognizes Martin Luther King Jr. Day. This day is set aside to remember the life and legacy of the martyred civil rights leader. Popularly, the holiday is filled with renditions of his famous “I Have a Dream” speech and vague, surface-level descriptions of Dr. King, but he was much more than this in his life. Dr. King was a multifaceted, complex, and flawed character who often failed more than he succeeded. In similar ways to the remembrance of King’s character, the history of his holiday has been vastly oversimplified. As one of three people with a federal holiday, this is no small feat. This is especially true as around fifteen years before the establishment of MLK Day, King was unpopular with many white Americans. According to a Pew Research Center poll, only 27% of white Americans held a favorable view of King in 1966 compared to 83% of Black Americans. Considering this, how was MLK Day established?

Fifteen years before the King holiday was federally recognized, Dr. King was assassinated on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee. In the week after his assassination, the Civil Rights Act of 1968 (Fair Housing Act) was passed, largely in reaction to the recent death of King as he had spent his last years advocating against housing discrimination. Less recognized at the time was a holiday bill proposed by Congressman John Conyers that gained little traction in Congress. Over the years, this changed, and by the Carter administration, Congress would hold its first hearings on the proposal.

Most notable about the support for the holiday during this period was its bipartisan character. This was so significant in fact that when conservatives like Democrat Larry McDonald and Republican John Ashbrook raised attacks against King’s character, alleging communist affiliations, they were sidelined and dismissed. Even more demonstrative of the changing attitudes towards King was that Ronald Reagan, infamously opposed to the liberalism of the sixties, ultimately signed the national King holiday into law on November 2, 1983. Reagan stated at the signing ceremony at the White House Rose Garden, “Dr. King had awakened something strong and true, a sense that true justice must be colorblind…”

The swift change in perceptions of King was reflective of the immense work and dedication of people like Coretta Scott King, Dr. King’s widow. Immediately after King’s assassination, Scott King and other civil rights leaders who had known King intimately got to work enshrining his legacy. The attempts at substantive memorialization by Coretta Scott King, Ralph Abernathy, and many others, such as the Poor People’s Campaign encampment in Washington, D.C., were unsuccessful in achieving tangible gains. In reflecting on her involvement with promoting a King holiday in her memoir, Scott King stated that there was much more enthusiasm for a holiday than for any other attempts at continuing King’s work. To promote the holiday, Scott King hosted rallies and marches, as well as collected hundreds of thousands of signatures. Famous Motown singer Stevie Wonder even wrote the song “Happy Birthday” to rally support for the national holiday. These years of hard work by Scott King and others not only produced a federal holiday but also created a positive image of King among politicians and the general American public.

Despite this, the creation of the federal holiday, along with the work to habituate King’s image had, and continues to have, great ramifications. For one, the establishment’s bipartisan support for the holiday overshadowed the bipartisan antagonism that had existed only a few years prior. Conservative politicians like Reagan, who had opposed civil rights legislation during King’s time and in the then present, were able to present themselves as sympathetic to the plight of Black Americans. Even liberal politicians, who were often just as antagonistic to King as conservatives, had something to gain from supporting the federal holiday. Jimmy Carter’s support for the holiday was at least in part driven by opposition within his own party for the presidential candidacy. The more popular Dr. King and the movement for a federal holiday became, the more necessary it was for politicians to show support for a federal holiday.

There is also something to be said about the aspects of King that were lost in his elevation to a national hero. In Coretta Scott King’s attempts to create a version of King that was palatable enough for a holiday, there were parts of Dr. King that were overemphasized and others that were not. King’s dedication to nonviolence, though a large part of his ideology, was the most emphasized aspect of him and would eventually become the sole defining aspect of the popular figure. Martin Luther King Jr. getting a national holiday put him on the same level as only two other people in the United States, Christopher Columbus and George Washington. These two men are part of the American saga: no longer real people, but essentially folksy bedtime characters. Though Washington and especially Columbus’s characters have been called into question in recent decades, it is undeniable that they have been made into shallow, mythical characters, and King has not been excluded from this process. Who gets holidays? Definitely not a man remembered for breaking with the Johnson administration on the Vietnam War and revealing the hypocrisy of liberal politicians, or a man who strongly critiqued American capitalism and militarism.

How a person is remembered, and the context they are framed in is very important to understanding both the past and the present. The ways that we choose to remember reveals more about oneself than it does about the thing or person that is being remembered. Yes, King was an extraordinary orator and civil rights leader, but he also had deep complexities. He was not a lone fighter in a war to cleanse America’s evils, but a man who was a part of a larger movement made up of dozens of organizations, hundreds of notable figures, and thousands of unnamed people, all of whom believed that a better world was possible.

A personal favorite quote about King comes from Vincent Harding’s book Martin Luther King, the Inconvenient Hero, where he states, “Somehow, King seemed easier to manage as a hero.”So for this MLK Day, let’s not just accept the easiest, most digestible story, but remember actively and intentionally in ways that are both hard and make us uncomfortable. This means moving beyond simply recalling the well-known parts of King’s “I Have a Dream” speech, but also considering King’s critiques of gradualism and his thoughts on what America owed to its most marginalized citizens. Other works of King to consult that are significantly relevant are his speech “Beyond Vietnam,” his “Letter from a Birmingham Jail”, and his last book, Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community? To get active in the local community for this upcoming MLK Day, the city of Mobile’s website, “cityofmobile.org”, has numerous volunteer clean up events available on the city’s website.