Article by: Nakeria Woods, Contributing Writer

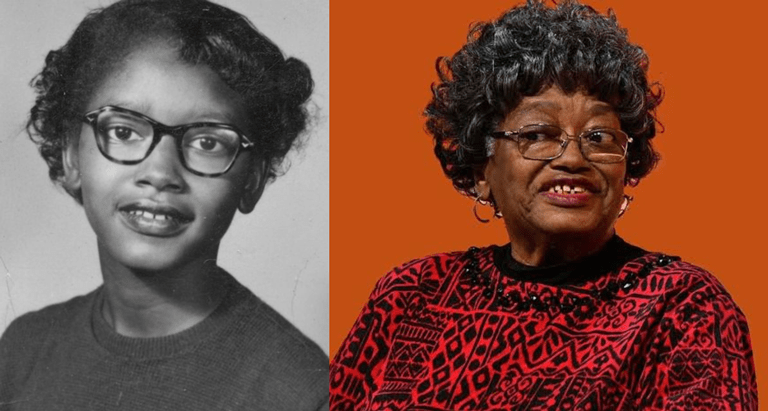

On January 13, 2026, Claudette Colvin, a pioneer in the larger American civil rights struggle, passed away at 86. Colvin was closely tied to the Montgomery Bus Boycott, a moment in civil rights history that some look at as the official start of the Civil Rights Movement. Despite this, her name has largely been lost to history, at least by the wider American public. This becomes unsurprising when one recognizes that, though the Montgomery Bus Boycott is one of the most recalled events in the Civil Rights Movement, it has been largely misremembered and misunderstood.

In J. Mills Thornton’s book Dividing Lines: Municipal Politics and the Struggle for Civil Rights in Montgomery, Birmingham, and Selma, he explained that racial segregation of public transportation was required in Montgomery by an ordinance introduced by Alderman John G. Finley in 1900. The Finley ordinance stated that conductors must maintain segregation through personal assignment to seats, and refusal to sit in an assigned spot would result in a misdemeanor. Thornton explains that “[t]hough the city was left with the Finley ordinance of 1900 as the only municipal legislation on the subject [of segregation],” the city actually followed the local bus company’s policy of segregation. This bus policy differed from the local legislation in that it reserved bus seats for white patrons and compelled Black passengers to move to accommodate oncoming white passengers even when no other seats were available. These two ordinances made the power of bus drivers very ambivalent.

All of this leads to the situation that would arise decades later in the fifties. When recalling the Montgomery Bus Boycott, many would typically begin with the 1955 story of Rosa Parks, but challenges to bus segregation in the city started long before this. Collective attempts to change busing segregation in Montgomery began years earlier in 1952 when local Black leaders asked the city commission to adopt Mobile, Alabama’s segregated seating plan.

This plan, though still enforcing segregation, did not have a strict dividing line between Black and white people, but would be adjusted as the racial composition of the bus changed. Essentially, the local Black leaders of Montgomery were asking for a “fairer” form of segregation. In an election for the Montgomery commission, Clyde Sellers, a candidate in this election, responded to these demands by asserting that this new seating proposal violated state law. Sellers’ sentiments resonated deeply with some white citizens of Montgomery due to a recent event that had taken place on a bus.

That event was the arrest of a 15-year-old Claudette Colvin a week earlier. On March 2, as Colvin was returning from school, she refused to leave her seat and stand to accommodate oncoming white passengers. She and Ruth Hamilton were seated on the very last row of the bus, but the bus policy in Montgomery allowed for the bus driver to demand that the two Black patrons stand, which Colvin refused. Ultimately, Colvin was arrested and charged with violation of bus segregation, disorderly conduct, and assault and battery of a police officer. She would plead not guilty and go to trial on March 18, defended by Fred D. Gray, Montgomery’s second Black attorney.

In this trial, Colvin was found guilty of the violation of bus segregation and assault and battery of an officer, which Gray appealed to the circuit court. When the case came to trial again on May 6, the state dropped its segregation charge, removing Gray’s ability to attack the segregation laws that existed within Montgomery. He considered having Colvin federally sue the bus company, but Colvin’s parents did not follow through due to embarrassment over Colvin becoming pregnant.

Colvin’s story was important to the beginnings of the Montgomery Bus Boycott for several reasons. For one, her arrest helped to renew attempts by Black leaders in the city to deal with busing segregation and brought questions about Montgomery’s busing laws into the forefront. Colvin would be the first in a long line of Black women in 1955 who would be arrested for segregation in Montgomery, the last one being Rosa Parks in December. Gray would file a federal court action for four of the women, including Colvin, against Montgomery officials and the Montgomery bus company on the basis of the unconstitutionality of bus segregation laws. In the case of Browder v. Gayle, the three-panel District Court for the Middle District of Alabama ruled that segregation in public transportation was unconstitutional, violating the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment. The Supreme Court upheld this decision, and on December 20, 1956, Montgomery officially desegregated its public transportation, upending over half a century of practice in the city.

The desegregation of Montgomery buses also led to the Montgomery Bus Boycott ending after 381 days. Though the court case is officially what desegregated public transportation in Montgomery, the Montgomery Bus Boycott was a huge galvanizing force and gained significant media attention for the issue of segregated buses in the city.

What eventually became lost in the larger narrative of the Montgomery Bus Boycott were the young ladies who were a part of Browder v. Gayle, including Colvin. There are several reasons for this, the most obvious one being that Rosa Parks dominates this narrative. This was not a mistake, but very intentional on the part of Black organizers in the city. Many of Parks’ attributes, such as her being an adult, the secretary of the local Montgomery NAACP branch, and being an overall image of Black middle-class respectability, made her a much more fitting figure to rally a movement around in the eyes of local Black leaders. And so they did, creating the Montgomery Improvement Association to officially run the boycott after a very successful first day of a bus boycott.

Colvin, on the other hand, was young, pregnant, had a darker complexion, and was perceived by many as too rowdy. She reflected that her mother told her, “Let Rosa be the one. White people aren’t going to bother Rosa—her skin is lighter than yours, and they like her.”

The Montgomery Bus Boycott would be reflective of the larger Civil Rights Movement in the ways that it relied heavily on image and its outward perception to garner sympathy and support. Recognizing this does not diminish the work of the many activists and leaders who helped craft this movement, but it does bring into question who or what is left behind. Claudette Colvin bravely defied a precedent that was many times older than her, helping to kick start one of the most recognizable local movements of the Civil Rights Era. Even at her young age, she felt a sense of duty, saying, “Harriet Tubman’s hands were pushing me down on one shoulder and Sojourner Truth’s hands were pushing me down on the other shoulder.” It is important to remember the courage of Colvin and how central she was to one of the first successful attempts to collectively oppose Jim Crow. To learn more about Claudette Colvin, you can read her 2010 biography, Claudette Colvin: Twice Toward Justice.